Within months of the release of AI-powered chatbot ChatGPT in late 2022, AI moved from specialist interest to topic of mainstream discussion. But which Australians are using generative AI (GenAI) tools? And how are they using them? Who is paying for premium tools? And is the use of GenAI following established patterns of digital inclusion, or creating new opportunities?

In 2024, the ADII introduced new questions to track GenAI use for the first time. We asked whether people had recently used one of these tools, what they used it for and whether they had paid for access to premium features. Unlike many other surveys of GenAI use, our survey reaches a higher portion of digitally excluded groups.

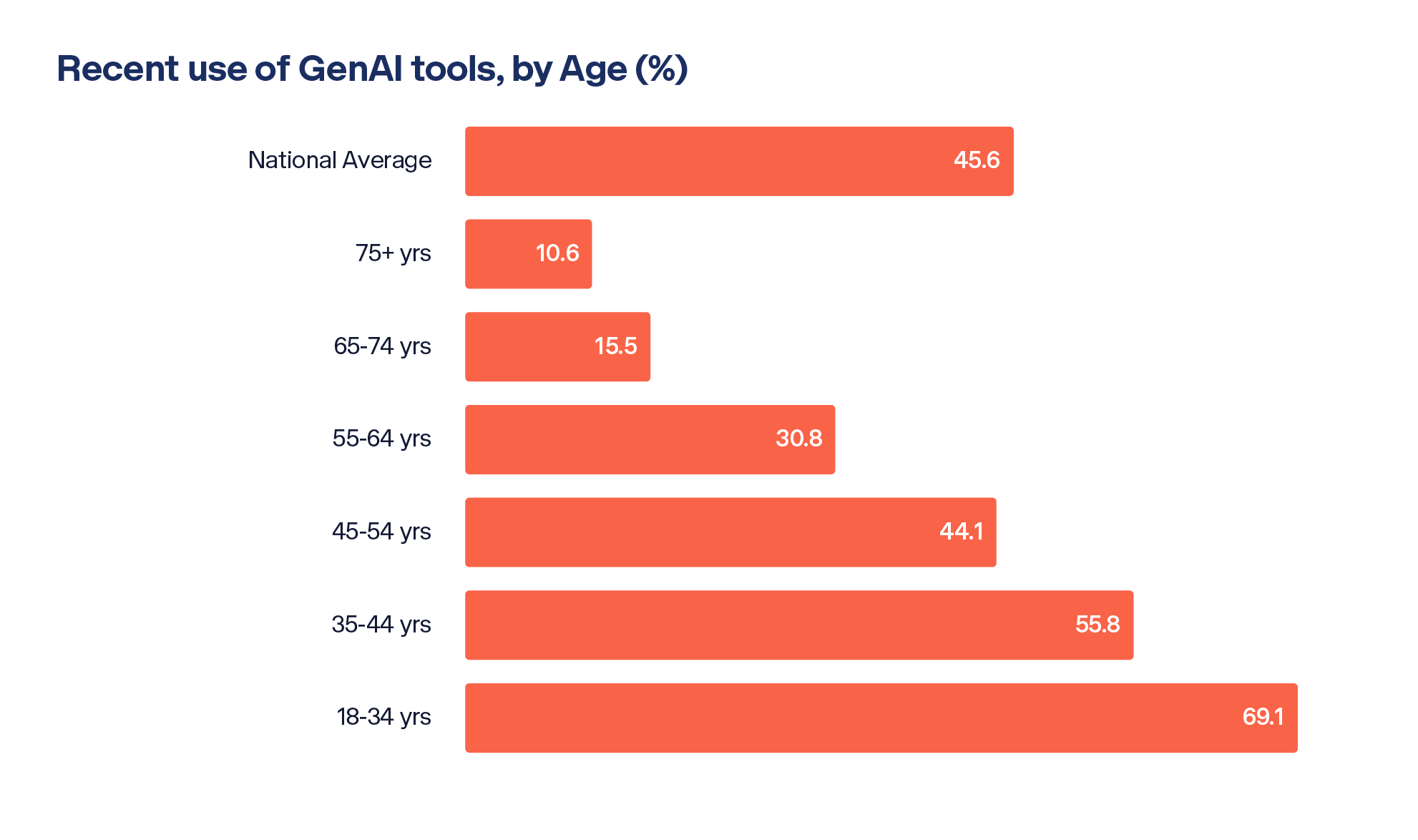

We found that almost half (45.6%) of Australians have recently used generative AI tools.

However, age, education, location and household situation shape who is using AI, who stands to benefit and who is already missing out as AI systems become a normal part of our digital lives. As GenAI tools rapidly evolve and become integrated into standard internet services like search, or help people communicate in text or images, and as chatbots become familiar interfaces for services, there is an urgent need to monitor who benefits and who is left behind. To adjust to these changes, we’ll also see important shifts in digital skills, making Digital Ability a key indicator of how AI tools will affect digital inclusion.

Who is using GenAI?

Younger Australians are more likely to use GenAI, with over two thirds (69.1%) of 18-34 year olds recently using one of these tools compared with less than 1 in 6 (15.5%) 65–74 year olds (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Recent use of GenAI tools, by Age (Source: Australian Internet Usage Survey, 2024).

People who speak a language other than English at home report higher use (58.8%) than English-only speakers (41.4%). This may be associated with improvements in the capabilities of AI tools for translation or accessing information in multiple languages.

Around a third of people with disability (33.9%) have used GenAI, with strong use of these technologies among this group for entertainment and advice.

Level of education and type of profession shapes GenAI use. GenAI tools have become part of learning and study at school, university and vocational training, and are rapidly changing knowledge work. Students are heavy users of GenAI (78.9%). People with a bachelor’s degree (62%) are much more likely to use GenAI than those who have completed high school (37.2%). Those who have left school at year 10 (4.2%) are some of the lowest GenAI users.

Professionals (67.9%) and managers (52.2%) are far more likely to use these tools than machinery operators (26.7%) or labourers (31.8%), suggesting strong links to occupational roles and contexts.

These differences show distinct patterns in GenAI use across demographic groups, reflecting variations in access, skills and contexts of use already observed in other areas of technology use.

How are Australians using GenAI?

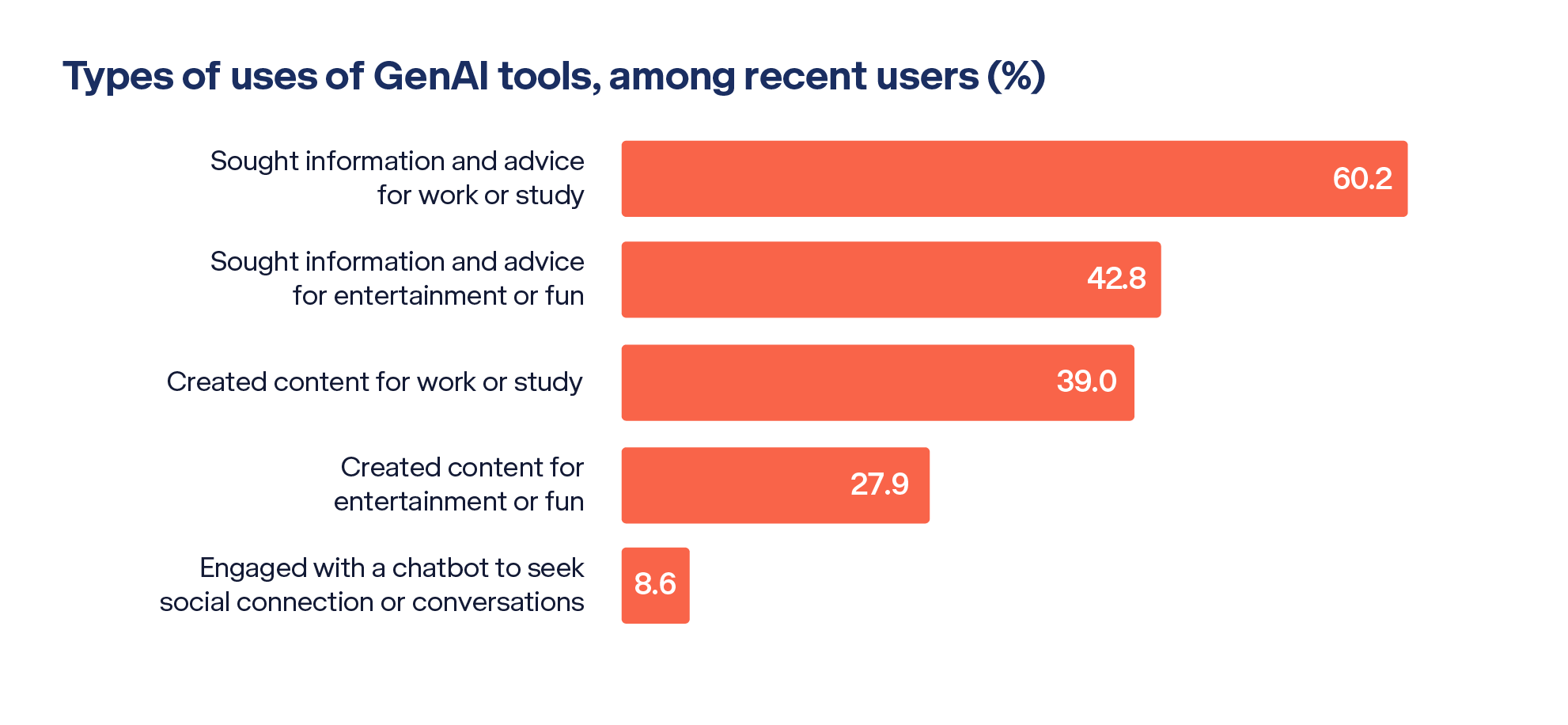

While those who are using GenAI are more likely to be using it to generate text (82.6%) than images (41.5%) or creating programming code (19.9%), we know far less about how these tools are being woven into everyday life. Their integration into work, learning, everyday decision making and even companionship is uneven and still emerging. We asked about usage for study and work, for entertainment and fun, and for conversations and social connection (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Types of uses of GenAI tools, among recent users (Source: Australian Internet Usage Survey, 2024).

Use of a chatbot for social connection or conversations is low overall (8.6%). Interestingly, we found that this usage of GenAI increases with remoteness, with GenAI users in remote areas (19%) more than twice as likely to use chatbots in this way than those in metropolitan areas (7.7%).

13.7% of Australians are paying for premium or subscription GenAI tools, with 18–34 year olds most likely to be paying (18.1%), followed by 45–54 year olds (13.1%).

What does GenAI mean for digital inclusion?

It’s not surprising that young people, students and professionals are making more use of GenAI. Many GenAI tools like Copilot, ChatGPT, Gemini and Midjourney are designed to be integrated into study and business with the claim of boosting productivity and enabling new forms of automation.

The higher uptake by those who speak a language other than English at home suggests that AI capabilities in translation may be providing new opportunities. However, people with disability (33.9%) and First Nations people (36.6%) are less likely to be using GenAI. This finding and the demographic patterns in GenAI use noted above suggest that GenAI will follow and potentially deepen existing digital inequalities.

Digital Ability is critical for GenAI use. GenAI tools work best when people know how to ask the right questions, judge the quality of information and manage how information put into these systems is managed. These are the kinds of skills the ADII tracks under Digital Ability. We ask participants, for example, whether they know how to check if information is trustworthy, or manage how much personal data they share online. However, these skills remain unevenly distributed, with older Australians and people with disability scoring particularly low on this cluster of skills.

Supercharging scams. People with lower levels of Digital Ability may be less likely to benefit from AI, while also being more vulnerable to new risks. This includes misleading content, scams and invasive data practices. There are rising concerns about the role of GenAI in online scams and inauthentic communication across websites, email, voice AI phone calls, social media or messaging. In a key international survey, cybersecurity and misinformation make up two of the top concerns people have with GenAI, with around half having observed or experienced these risks [1].

AI, education, learning and work. New forms of media literacy and AI literacy will be needed to navigate the influx of AI generated internet content. This will inevitably dent the confidence of people with lower levels of ability and those who are less frequent internet users. A recent national media literacy survey showed that a majority of adult Australians desire more media literacy support beyond school years or formal education [2].

New affordability challenges. Access to premium AI tools often requires a paid subscription. This has consequences for who can afford and benefit from these tools.

As GenAI becomes embedded in search, productivity software and social platforms, differences in uptake and skills can translate into unequal access to information, services and work. The ADII’s new GenAI questions—alongside long-standing measures of Access, Affordability and Digital Ability—provide a baseline for tracking who uses these tools, what they use them for and who pays for access to premium features. Monitoring these patterns over time and across regions and demographic groups will help governments, industry and community organisations target support, evaluate programs and assess how broadly the benefits of AI are being shared.

References and footnotes

[1] Gillespie, N., Lockey, S., Ward, T., Macdade, A., & Hassed, G. (2025). Trust, attitudes and use of artificial intelligence: A global study 2025. University of Melbourne and KPMG. https://doi.org/10.26188/28822919

[2] Notley, T., Chambers, S., Park, S., Dezuanni, M. (2024). Adult Media Literacy in 2024: Australian Attitudes, Experiences and Needs. Western Sydney University, Queensland University of Technology and University of Canberra. https://doi.org/10.60836/n1a2-dv63